No Thrones. No Crowns. No Kings. →

On October 18, millions of us are rising again to show the world: America has no kings, and the power belongs to the people.

The unsupported use case of Bix Frankonis’ disordered, surplus, mediocre midlife in St. Johns, Oregon—now with climate crisis, rising fascism, increasing disability, eventual poverty, and inevitable death.

Read the current manifesto. (And the followup.)

Rules: no fear, no hate, no thoughtless bullshit, and no nazis.

On October 18, millions of us are rising again to show the world: America has no kings, and the power belongs to the people.

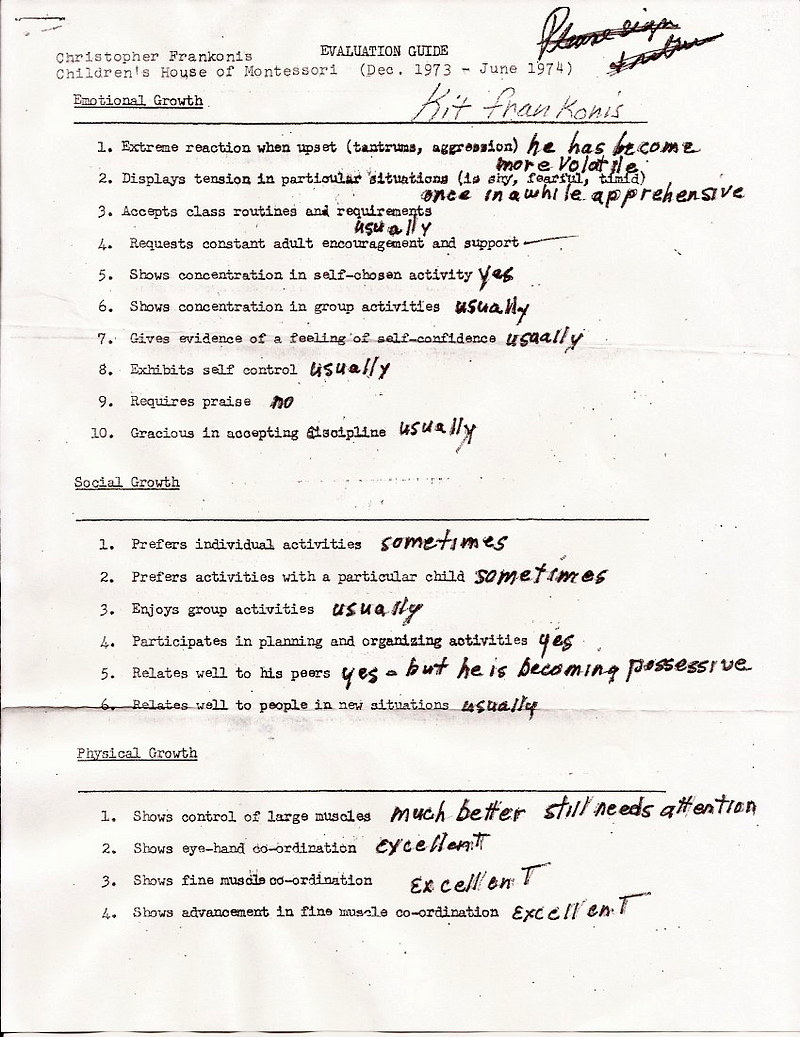

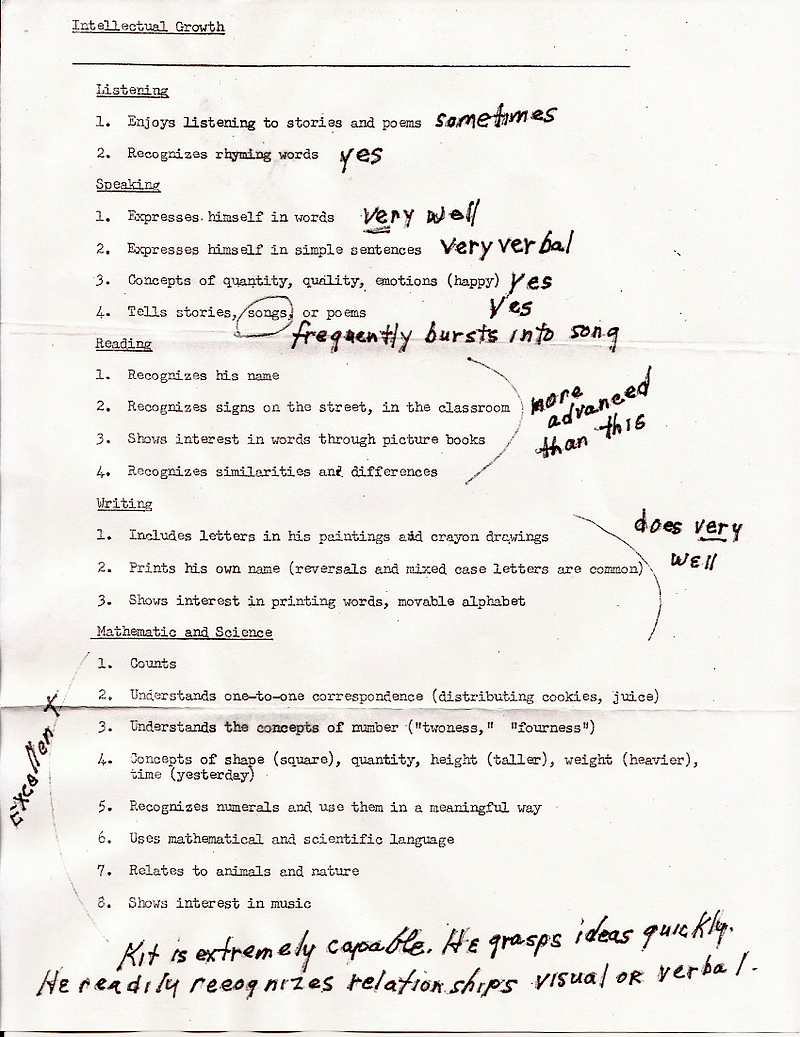

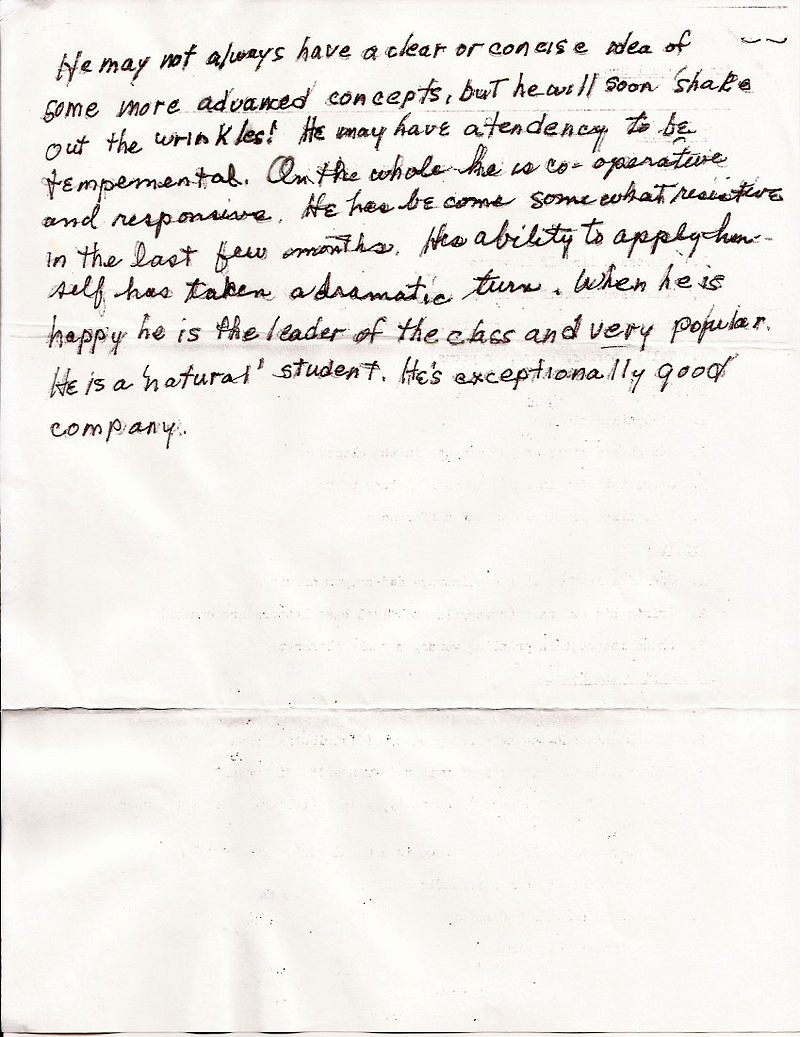

Somehow in the transition from Medium to Write.as to Micro.blog to WordPress, one thing that never made it across from the start of the chain was a post about the June 1974 evaluation I received from my Monteossori school when I would have been four-years-old.

I’d wondered how that 1974 evaluation related to my October 2016 diagnosis as autistic, professing that I’d no idea. I know that I’ve been confused about some of elements which I suspect some might read as evidence contradicting an autism diagnosis, and that’s been nagging at me—in the sense that I’m convinced that any tiny scrap of evidence which superficially suggests that I can “deal” will be used against me as in the second half of my life I inevitably fight for support and assistance.

(Over the years, I’ve stumbled across this evaluation and I seemed to focus on the same elements, such as “he has become more volatile” and “frequently bursts into song”; I’ve wondered if the latter explains in more recent years singing “where’d the breeze go” to the tune of “Hang the DJ” or the song I’d sung about being cold which included the lyrics, “motherfucker motherfucker motherfucker”.)

Somewhat randomly today, as I was reading Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement, it occurred to me that perhaps the relation is simple: the Montessori approach simply was more accommodating to autistic thought and behavior. Which is not to say this would be the case for any autistic (just as it wouldn’t be the case for every neurotypical); it just seems to me now that it makes sense in my case.

What set me off on this revisit was the book’s chapter on “Lobbying Autism’s Diagnostic Revision in the DSM-5”, in particular its references to mitigation and accommodation. Much like my most successful periods of employment unknowingly involved accommodations (e.g. working with people with whom I’d previously established social relationships with), and much like many of my most intense and involved avocations (e.g. fandom activities) featured broadly-accepting social and behavioral milieus, so, too my Montessori experience in a sense “masked” my behavioral, communication, and social styles simply by accepting them as a natural given.

In none of these circumstances did anyone know that I was autistic, as the diagnosis wouldn’t come until my mid-forties, but it’s helpful—and this is how that chapter sent me thinking—to be able to point out that just because one sometimes finds environments in which being autistic isn’t an obstacle it doesn’t mean you’re somehow not autistic or not in need of supports.